AIDA YOUTH CENTER

Together we make creative changes معاً بإبداع نصنع التغيير

History of Palestinian Refugees

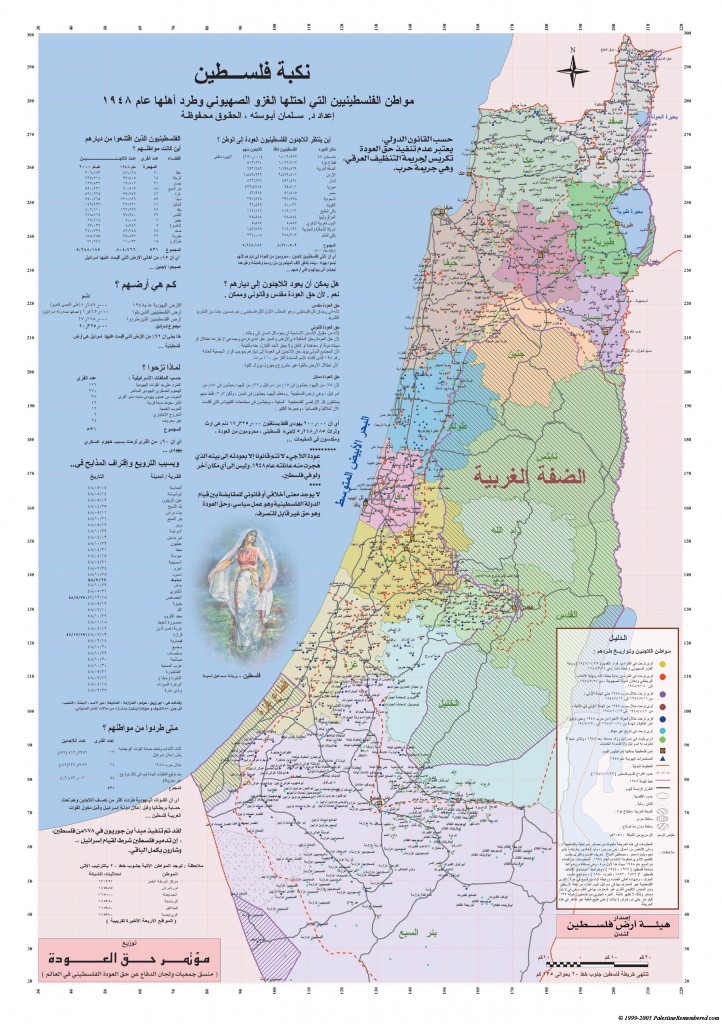

The modern history of Palestine has been marked by wars, displacement and instability. Beginning with the British Mandate in the early twentieth century, the Balfour Declaration in 1917, the 1948 War that led to the illegal establishment of the State of Israel, and the displacement of Palestinians from their homeland, a new reality has been forged for the Palestinian people.

In 1917, during the First World War, Britain offered its support to British Zionist organizations for the establishment of a future Jewish state in Palestine. From 1920 – 1948, Britain administered Palestine on behalf of the League of Nations in what was known as the British Mandate of Palestine. Following the Second World War, the increasing costs of the British Mandate, combined with the unrest sparked by mass Jewish immigration, caused Great Britain to announce that it would withdraw its control from the area in 1947. The British Administration handed over its Mandate to the United Nations, which had replace the League of Nations, on the 15th of May, 1948, leaving a power vacuum in Palestine waiting to be filled.

One day before the Mandate was due to expire, the Jewish Agency declaration the existence of the new Jewish State of Israel, on May 14, 1948, in what is known to Palestinians as Al-Nakba, or the Catastrophe. During the ensuing 1948 Arab-Israeli War, as well as the Civil War that preceded it, 750,000 Palestinians fled, or were forced to flee, from their homes because of the conflict. This mass exodus was the result of a number of factors. First, Zionist militant groups such as Irgun and Lehi carried out indiscriminate attacks on the civilian population during 1947-8, and Palestinian villages such as Al-Maliha were attacked by the Irgun. Following the withdrawal of British Forces, and the Israeli Declaration of Independence on May 14, 1948, expanding Israeli military operations forced many more people to flee. One example would be Operation ha-Har, which aimed to occupy a number of villages in the southern half of the Jerusalem corridor. Many refugees living in the Aida camp are from villages that were depopulated as a result of this operation, including Allar, Beit Nattif and Ras Abu Ammar. Their inhabitants were either forcibly expelled or fled under pressure as many of their homes were demolished. Such attacks and military operations also had a domino-effect on surrounding areas where Israeli propaganda encouraged Palestinians to leave their homes before further military incursions occurred.

In 1949 the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) was established by the United Nations General Assembly, Resolution 302 (IV), in order to provide relief and humanitarian services to the refugees. Palestinian refugees now live in five main areas: the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), the Gaza Strip and the neighboring Arab countries of Jordan, Syria and Lebanon. There are also many more that, over time, fled further afield. The refugees’ lives were far from stable, and many spent their early years of displacement constantly on the move, shifting from place to place in an attempt to find safety. In addition to those refugees who fled or were expelled because of the 1948 War, another 300,000 Palestinians were made refugees following the Six-Day War in 1967. This group included many who were already refugees from the initial conflict.

Today there are 4.8 million Palestinian refugees registered with UNRWA [1], and 450,000 Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) that remain in Israel, but are still not allowed to return to their original homes. Approximately one third of the refugees, 1.4 million, live in 58 UNRWA-recognized refugee camps, and many more live in a small number of non-registered camps. The refugees represent 70% of the entire Palestinian population worldwide; two out of every five refugees in the world today are Palestinians. Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) represent the largest and longest-standing case of forced displacement in the world today.

The Right to Return:

The refugees living in Aida Camp today, as well as those living throughout the Palestinian territories and surrounding countries, are still awaiting a solution to their problem and a chance to return home. The construction of “The Largest Key in the World” at the entrance to Aida Camp is a peaceful, symbolic representation of this Right to Return. Under international law, all individuals possess “the right of return” – that is, the right to return to their homes of origin when they have been displaced due to circumstances beyond their control. In the specific case of the Palestinian refugees, the right of return also has its basis in UN resolutions passed following the declaration of the state of Israel in 1948.

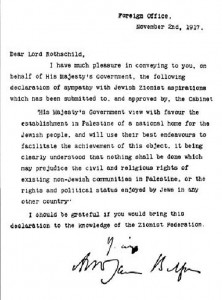

Even before the declaration of the state of Israel, there was precedent from the British Government, which administered Palestine under a League of Nations Mandate from 1920 – 1948, stating that establishing the country as a “national home for the Jewish people” should not negatively affect the lives of the Palestinians already living there. In the Balfour Declaration of 1917, the British Government declared that:

“His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people… it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine…”

Following the Arab-Israeli War in 1948, the United Nations passed Resolution 194 (passed December 11, 1948) dealing with the situation in the region of the British Mandate of Palestine. Article 11 explicitly calls for the return of the Palestinian refugees and is quoted below:

“Resolves that the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which, under principles of international law or in equity, should be made good by the Governments or authorities responsible.”

The refugees are still waiting for this resolution to be enacted. Though it should be noted that General Assembly Resolutions are not binding, and act only as advisory statements, Israel’s admission to the UN in 1949 was conditional upon its acceptance of all UN resolutions, including Resolution 194. Furthermore, Article 11 specifically states that Israel is obligated to ensure the return of the refugees. It also states the exact place of return (their original homes) and that the return is determined by the individual decision of the refugee (“wishing to return…“).

The right to return is also recognized in article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states:

“Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and return to his country.”

It is clear under international law that a change of sovereignty does not change or diminish personal rights of ownership, nor does it change an individual’s citizenship in the land historically known as “his country.” Furthermore, under the Law of State Succession, when a geographical territory undergoes a change of sovereignty, the habitual residents of that geography should be offered nationality by the new state.

The International Law Commission, which is a UN body of legal experts, has published a series of articles on Nationality/State Succession which clarifies the status of “habitual residents.” In Article 14, they clearly state that “the status of persons concerned as habitual residents shall not be affected by the succession of States.” Furthermore:

“A State concerned shall take all necessary measures to allow persons concerned [i.e., habitual residents] who, because of events connected with the succession of States, were forced to leave their habitual residence on its territory to return thereto.”

The ILC also states in a later article that such residents are also presumed to have the nationality of the successor state.

It is therefore clear that the Palestinian refugees, as residents of the geographical territory of Israel prior to 1948, have the right to return to their original homes. This remains true, regardless of whether the situation is viewed from a political, a legal or a humanitarian perspective.

The Right of Return is not only a legal right for the Palestinian refugees; it is feasible and possible. Demographic studies have shown that 78% of the Jewish population of Israel lives on just 15% of the land, with the majority occupying urban areas similar to those inhabited by the Jews in pre-1948 Palestine. Only 154,000 rural Jewish residents (2% of the total population) control the areas that are essentially the land belonging to the Palestinian refugees. In addition, many villages, such as Imwas, Yalu, Beit Nuba and Kafr Bir’im in the north, are now the sites of National Parks. See here for more information on the feasibility of the Right of Return.

For more information on ‘the right to return’ and the case of the Palestinian refugees, please refer to BADIL’s The 1948 Palestinian Refugees and the Individual Right of Return: An International Law Analysis (BADIL, 2007).

[1] “Under UNRWA’s operational definition, Palestine refugees are people whose normal place of residence was Palestine between June 1946 and May 1948, who lost both their homes and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 Arab-Israeli conflict.